Canadian Court Gives 👍 to Contract Accepted by Emoji

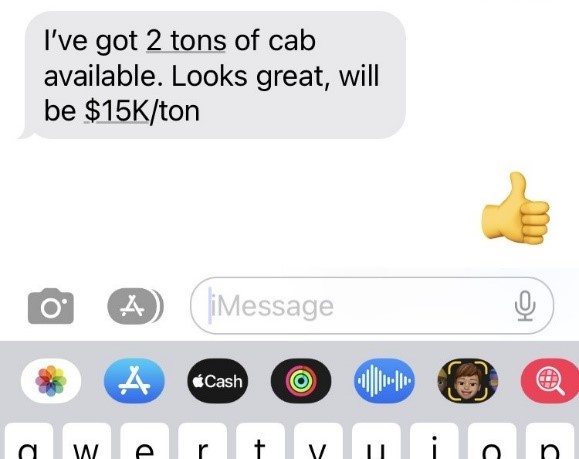

Harvest is underway in wine country. During this season there is increased demand for skilled labor, transportation, and crush facilities. Buyers and sellers of fruit have a short window to make deals. A busy harvest season also lends itself to casual communication about crops, like this:

Now, did you just tell your friend you are happy for him, or did you just commit to buying $30K worth of fruit?

According to at least one Canadian court, the thumbs-up 👍 emoji could qualify as acceptance of a contract. A recent decision from the Court of King’s Bench in Canada discussed the “new reality in Canadian society” facing courts as the forms of communication broaden.

The Canadian court examined a dispute between a farmer and grain buyer over an alleged contract for 87 metric tons of flax, to be delivered in November 2021. The grain buyer and farmer spoke by phone, and the buyer texted the farmer a photo of the contract signed by buyer for November delivery. The text message said “please confirm flax contract.” The farmer texted back a “thumbs-up” emoji.

Later, when November rolled around, the price of flax had gone up, and the farmer attempted to say that his “thumbs-up” in response to the buyer only signaled that he had received the contract, not that he had accepted it. The court also looked at the prior dealings between the farmer and buyer, noting that in prior contracts for durum wheat, the farmer had various formed agreements with the buyer employing similarly concise responses, including “looks good,” “ok,” or “yup.”

Here, the court ultimately found that yes, the “thumbs-up” was sufficient acceptance, and the farmer was ordered to pay C$82,000 for the unfulfilled contract.

Canadian law is not controlling in the United States. However, this case reminds us that as forms and methods of communication grow, U.S. courts may eventually find that an emoji can qualify as acceptance of an agreement.

So, during important business negotiations, consider the potential consequences of casually firing off that “thumbs-up” emoji to the other side. Finally, when in doubt, seek the advice of an attorney.

Always Read The Contract – They Wrecked Your Wine, But Now Won’t Pay

You send your Chardonnay to a custom crush facility for bottling. A month later the wine in one out of about every ten bottles is brown. It oxidized in the bottle. You are forced to pull all your Chardonnay from the market at significant expense, and you fear your brand has suffered. The evidence suggests that the wine oxidized during bottling. Surely, the custom crush facility will step up and compensate you for your damages? To the surprise of many vintners, the custom crush facility may escape much or all liability based upon language in its contract.

In California, as in most states, companies can dramatically limit their liability to commercial customers. Companies do this by including clauses in their contracts with customers that exclude liability for negligence, for lost profits, or for consequential damages, among other things. These clauses are powerful – if something goes wrong – like oxidized wine – these clauses can shift liability from the company to the customer, or in our example, from the custom crush facility to the vintner. These clauses, if drafted properly, could prevent the custom crush facility from liability for lost profits, any damage to the vintner’s wine brand, consequential damages, and might even limit damages to the value of the wine if sold as bulk wine.

California courts will enforce contractual limitations of liability, but courts interpret those clauses very strictly. Consequently, those clauses should be well written and clear. There are, however, exceptions to the enforceability of these clauses. Parties cannot limit liability for fraud, willful injury to persons or property, or for violations of the law, even if those violations are negligent. While parties can limit liability for negligence, parties cannot limit liability for gross negligence. Courts explain that gross negligence is the “lack of any care or an extreme departure from what a reasonably careful person would do in the same situation to prevent harm to oneself or to others.” (See CACI 425.)

Additionally, contracts can further attempt to limit the amount of damages. For example, the custom crush facility in the above example might include a clause valuing the wine at $5 a gallon. If the wine is then destroyed in the bottling process because of the custom crush facility’s negligence, damages may be limited to $5 a gallon, even if the wine might retail for $25 a bottle.

If you are a winery or a winemaker in California, you need to understand these contractual limitations of liability before signing any contract with a custom crush facility, an alternative proprietor, bottler, or other service provider. You need to read the contract, and you further should understand that you could object to these limitations or negotiate less onerous clauses.

If you provide services to winemakers or wineries, you should also understand the need for contractual limitations of liability. Accidents happen, and they should not cost you your business. These limitations of liability, however, must be carefully drafted, and you should obtain an attorney with knowledge of the wine business to draft these limitations.

Additionally, all parties should understand the need for the right insurance to cover situations when things do go badly. Typically, commercial general liability policies will not cover damage to wine that occurs during the “wine making process,” which may include bottling. Both the vintner and the custom crush facility would do well to have an errors and omission policy.